7.7 ANALYSIS OFTHE ATTACHMENT TO GOD :

Attachment

with god and religion can be evaluated and it can be compared with childhood

attachment dynamics and some logical conclusion may be made.

Recent theoretical and empirical work by Lee

Kirkpatrick and others has suggested that relationship with God can be

fruitfully described as an attachment bond.

Empirically we can prove the differences between various group of

population[i]

. They have devised a scale called attachment to god inventory and have tested their hypothesis on people

and compared personality issues and

religios styles.

Attachment to God Inventory[ii]

(AGI) well provides tests of the correspondence

and compensation hypotheses. In general, the AGI subscales of Avoidance of

Intimacy and Anxiety about Abandonment display good factor structure, internal

consistency,and construct validity.

Comparisons of the AGI with adulthood

attachment measures appear to support, although weakly, a correspondence

between working models of romantic others and God. identification as a mother,

father, and a lover, it is less clear how an attachment model describes

Deity/Person relationships in other world religions, particularly if the Deity

is not thought of as “personal” in nature.

Empirical research concerning

attachment with God

The limited but growing empirical literature concerning attachment with

God and the relationship between

attachment styles and religiosity has suggested that attachment perspectives

are a fruitful line of investigation in the psychology of religion research[iii],[iv].

It is found

relationships between attachment style and religious variables such as religious

belief, commitment,and involvement; God image; conversion experiences.

In addition it has

been found evidence that God may serve as a compensatory attachment figure for

individuals displaying insecure attachment patterns. There is evidence that individuals may use God as a

substitute attachment figure; although

that this process may be more complex than previously thought. Others

have found relationships between adulthood attachment and spiritual maturity[v].

Assessing attachment to God and the

“compensation or correspondence hypothesis”

The empirical

research has suggested intriguing relationships between attachment variables

and religious constructs has been limited by the lack of a psychometrically sound instrument to assess

attachment to God.

This void has limited

researchers from addressing one of the more intriguing questions in this

literature. The “correspondence or compensation” question is an attempt to

determine

a) if

attachment to God basically mirrors the person’s caregiver and lover attachment

style (the correspondence hypothesis)

b) b) if

relationship with God helps the person compensate for deficient caregiver

bonds, where a relationship with God fills an attachment void (the compensation hypothesis).

As noted above, some evidence suggests that the compensation hypothesis

may be correct. However, other evidence building upon Object Relations theory,

suggests that the correspondence hypothesis may be correct.

Specifically, it has been

shown that positive relationships with caregivers are associated with more

loving and nurturing God images. Conversely, it appears that negative relations

with caregivers are associated with God being experienced as more demanding and

authoritarian.

These conflicting lines of

evidence suggest that researchers must be careful when framing the issue of correspondence versus compensation.

Specifically, there is a distinction between compensatory behavior (e.g.,

conversion, religious practices) and how an individual experiences

God (i.e., Is God perceived as loving and kind, or distant and judgmental?).

Within the

attachment to God literature, this issue is even more vexing due to the lack of

a psychometrically sound instrument assessing attachment to God. Consequently,

comparisons between attachment to God, God imagery, and compensatory religious

behavior cannot proceed until the psychometric issues are resolved.

The Attachment to God Inventory

Building upon attachment pattern classification

schemes for childhood bonds with

caregivers and adulthood love

relationships . It is argued that two

dimensions underlay most attachment classification models:

a)Avoidance of Intimacy

b) Anxiety about Abandonment.

Consequently, this model is dimensional in nature allowing individuals

to vary along the two continuous

dimensions of Avoidance and Anxiety.Yet, should one choose to use a typological

model,these dimensions can be dichotomized to generate the classic fourfold

typology of Secure, Preoccupied, Fearful, or Avoidant attachment.

The flexibility of this classification model is clear in that it can

incorporate both dimensional and typological schemes of attachment

classification.

To

synthesize the wide variety of adulthood attachment measures used by

researchers, and to operationalize the Avoidance and Anxiety dimensions, the

study wanted to develop a measure that assessed the attachment dimensions of

Avoidance of Intimacy and Anxiety about Abandonment as they apply to

relationship with God.

Consequently, the Experiences in Close Relationships scale became a

model for our Attachment to God Inventory (AGI). Our conceptualizations of the

Avoidance and Anxiety dimensions as they apply to relationship with God were

straightforward and paralleled descriptions other studies.

Specifically,

Avoidance of Intimacy with God involves themes such as a need for

self-reliance, a difficulty with depending upon God, and unwillingness to be

emotionally intimate with God.

In contrast, Anxiety over

Abandonment involves themes such as the fear of potential abandonment by God,

angry protest (resentment or frustration at God’s lack of perceived affection),

jealousy over God’s seemingly differential intimacy with others, anxiety over

one’s lovability in God’s eyes,and, finally, preoccupation with or worry

concerning one’s relationship with God.

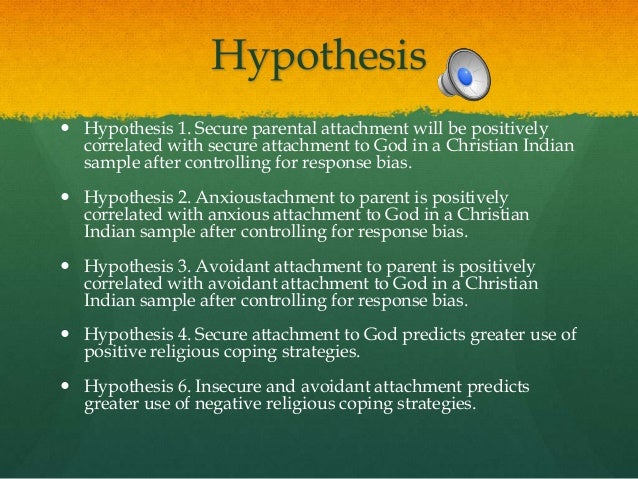

The study can be in three parts as done by Kirk

Patrick.et al.,

Study1: An overview

the scale construction and validation of the AGI.

Study 2:The AGI is then used to test hypotheses

concerning correspondence or compensation in

a college

Study 3: The AGI is then used to test hypotheses

concerning correspondence or compensation , in the adult community sample and

the faith group differences concerning attachment to God are explored

Since

relationship to God is often fostered within diverse religious communities, we

wanted to determine if the construct was stable across religious affiliation.

Assessing attachment to God

The main goal of the study -1 was

the development and validation of the Attachment to God Inventory and it was

observed to be good.

This scale was theoretically derived from and closely

parallels currently used adulthood attachment measures. Specifically, the AGI

has two subscales assessing the attachment dimensions of Anxiety

1)concerning potential

abandonment and lack of intrinsic lovability

2) Avoidance -avoidance of intimacy and compulsive

selfreliance.

These

two dimensions seem to underlay most attachment classifications schemes,

childhood and adult. This study suggested that they also might describe

attachment bonds to the God.

Relationship

with God may be characterized as an attachment bond. And yet, this

question demands continued theoretical

and empirical attention. The AGI was

developed to provide psychology of religion researchers a tool to more directly

assess attachment to God.

Correspondence versus compensation?

A secondary goal of this series of studies, was to use

the AGI ( attachment to god inventory) to

address the correspondence versus compensation hypotheses.

Do people seek out relationship with God to compensate

for deficient caregiver and adulthood attachment bonds? Or do people, when in

relationship with God, simply continue employing the same working-model they

use for all attachment bonds?

A trend was noted, it was for a correspondence between

the adulthood and God Anxiety dimensions.That is, in both Study 2 (a college

sample) and Study 3 (a community sample), the more attachment anxiety the

person reported in their love relationships, the greater their expressed

attachment anxiety in relationship with God.

Although findings tend to lean toward the

correspondence hypothesis, the

literature cited earlier were supporting the compensation hypothesis ? the data may be consistent with both

hypotheses. Specifically, individuals with deficient childhood and attachment

bonds may be attracted to or seek out an attachment to God to fill an

attachment void (compensation).

This idea is supported by Kirkpatrick’s observation

that insecure (anxious and avoidant) women were more likely over the

span of four years to report having “found a new relationship with God” or to

have had a conversion experience[vi].

However, once this relationship is initiated, previous

working-models may begin to assert themselves in this new relationship.

As noted earlier, this line of argument is also

supported by work using Object Relations Theory to understand relationship with

God . Specifically, this evidence suggests that object relations development is

related to God image.

In short, the motives to seek out and establish a relationship with God

may have compensatory goals. However, once the relationship is established, the

person’s working-models may tend to manifest themselves.

Consequently, in the literature we may see evidence

for both compensation (the need to fill an attachment void with a relationship

with God) and correspondence (the convergence of working-models across all

attachment bonds: Caregiver, lover, God.

Avoidance of intimacy

The trends for correspondence regarding the attachment

dimension of Anxiety were relatively clear,

however findings for the dimension of Avoidance were much more

equivocal. specifically, in Study 2 ( of

Kirckpatrick), AGI-Avoidance failed to converge on adulthood ratings of

Avoidance.

Since the

Avoidance dimension corresponds to a “negative views of others,” one might

expect that Avoidance ratings would be qualitatively different across

caregiver, lover, and spiritual attachment bonds. However, Avoidance themes are

present in relationships with God, specifically, discomfort with depending upon

God and with emotional displays of affection toward God.

In short,

although attachment Avoidance can

describe facets of relationship with God, this relationship is unique enough in

that demonstrating correspondence between working-models of others may be

difficult to establish (positive or negative views of: God vs. caregivers vs.

lover).

Future

directions

An obvious limitation in this series of studies, was

the exclusive focus on western religions. How well an attachment to God

framework generalizes to saivism, is an open theoretical and empirical issue.

From a theological point of view, one prerequisite for an

attachment bond to exist in a faith would be that the believer experiences God

as “personal” in nature and that the relationship with the Deity approximates

the criteria of an attachment bond-similar to one the child has with parents.

Of the major monotheistic world religions, Islam and

Judaism appear to have many of the features required to explore attachments to

God. It would be of interest to compare these and other religions to observe

how they might differ in their attachment bonds to God.

Depending upon the theological configuration of a

particular faith, that attachment frameworks in many cases would be unsuitable

in describing the experiences of certain groups of believers. It would also be

of interest to continue exploring faith group differences for attachment to

God.

The comparisons

in Study 3 ( by Kirckpatrick)suggest that within a religion, groups may systematically differ in their

attachment bonds with God. The causes for these differences probably result from different theological

worldviews which regulate how believers in a particular group view and interact

with God.

This

suggests that attachment to God may proceed in a developmental fashion as the

believer grows and interacts with a single faith group or, through the

lifespan, different faith groups.

We are particularly intrigued by how life

events might affect the attachment bond to God. Traumatic life events tend to affect

believers in unpredictable ways. Some (the Old Testament character Job comes to

mind), tend to turn to God as a haven of safety during difficult life

experiences.

Others may view the traumatic life event as evidence

of God’s disinterest, malevolence, or nonexistence. We expect that the prior

attachment bond may be predictive of how the believer would respond. Finally,

future research should also explore how early caregiver experiences affect or

are related to attachment to God.

God imagery appears to be driven by paternal and

maternal caregiving images Consequently,

comparing caregiver attachments, God imagery,and attachment to God may provide

a better test of the correspondence and

compensation hypotheses.

To conclude, due to work by Kirkpatrick and

others,increasing attention is being given in the empirical literature to the

attachment to God construct.Many interesting and, in some cases, longstanding,

questions continue to be debated or have yet to be examined quantitatively. The

Attachment to GodInventory is offered as a tool for researchers interested in

exploring this intriguing area of research.

NEED FOR SIMILAR SRESEARCH AMONG HINDUS AND SAIVITES:

Monotheistic religions like the Judaism,Christianity

or islam are not be taken very different from saivism. Saivism also preaches

monotheism.

We have to experiment with similar objectives in

saivite attachments too. This can be done retrospectively going through the

life of the individual nayanmaars or the important saints like

vallalar,patinathar,thayumanavar..etc.

Or else prospectively we can go through contemporary

saints and bakthars using similarly divised scales and find what kind of

attachment problem they have in mind. This would enable us more systematic

knowledge about the normal or abnormal style of progress of spiritual activity.

Saiva tenets clearly have demonstrated that the growth

of spirituality follows the steps we have seen so far like iruvinai

oppu,malabaribaham and sakthinibatham.

The normal attachments and the normal progress to

spirituality can be achieved only by the systematic following of the sadhana.

These sadhana are analogous to the psychotherapies of the west. The improper

method od merging with sivam may lead to such a pathological god attachment as

we see in the above mentioned nayamaars.

These methods

are well discussed in the pandara sastra texts. They take the individual in

stepwise fashion towards proper merger with the sivam. They are the PANCHKRA

PAHRODAI,DHASAKARIAM AND NITTAI VILAKKAM

. These sadhana methods will be seen in

the subsequent chapters in detail.

[i]

ATTACHMENT TO GOD: THE ATTACHMENT

TO GOD INVENTORY,TESTS OF WORKING MODEL CORRESPONDENCE, AND AN EXPLORATION OF FAITH GROUP DIFFERENCES;RICHARD

BECK Abilene Christian University ANGIE MCDONALD Palm Beach Atlantic University

Journal of Psychology and Theology2004, Vol. 32, No. 2, 92-103

[ii]

THE ATTACHMENT TO GOD INVENTORY

The following

statements concern how you feel about your relationship with God. We are

interested in how you gener- ally experience your relationship with God, not

just in what is happening in that relationship currently. Respond to each

statement by indicating how much you agree or disagree with it. Write the

number in the space provided, using the following rating scale:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Disagree Neutral/Mixed Agree Strongly Strongly

_____1. I worry a lot

about my relationship with God

. _____ 2. I just

don’t feel a deep need to be close to God

. _____3. If I can’t

see God working in my life, I get upset or angry.

_____4. I am totally dependent upon God for

everything in my life. (R)

_____5. I am jealous at how God seems to care

more for others than for me

. _____6. It is

uncommon for me to cry when sharing with God.

_____7. Sometimes I feel that God loves others

more than me.

_____8. My

experiences with God are very intimate and emotional. (R)

_____9. I am jealous at how close some people

are to God.

_____10. I prefer not

to depend too much on God

. _____11. I often

worry about whether God is pleased with me.

____12. I am

uncomfortable being emotional in my communication with God.

_____13. Even if I fail, I never question that

God is pleased with me. (R)

_____14. My prayers to God are often

matter-of-fact and not very personal.*

_____15. Almost daily I feel that my

relationship with God goes back and forth from “hot” to “cold.

_____16. I am uncomfortable with emotional

displays of affection to God.*

_____17. I fear God does not accept me when I

do wrong

. _____18. Without

God I couldn’t function at all. (R)

_____19. I often feel angry with God for not

responding to me when I want.

_____20. I believe

people should not depend on God for things they should do for themselves

. _____21. I crave

reassurance from God that God loves me.

_____22. Daily I discuss all of my problems

and concerns with God. (R)

_____23. I am jealous when others feel God’s

presence when I cannot

. _____24. I am

uncomfortable allowing God to control every aspect of my life.

_____25. I worry a lot about damaging my

relationship with God.

_____26. My prayers to God are very emotional.

(R)

_____27. I get upset when I feel God helps

others, but forgets about me.

_____28. I let God make most of the decisions

in my life. (R)

Scoring: Avoidance =

sum of even numbered items Anxiety = sum of odd numbered items Items 4, 8, 13,

18, 22, 26, and 28 are reverse scored * Researchers may want to consider

dropping these items (14 and 16).BECK and MCDONALD.

[iii]

J Relig Health.

2014 Dec 6. [Epub ahead of print],A Critical Comprehensive Review of

Religiosity and Anxiety Disorders in Adults.Khalaf DR1, Hebborn LF, Dal SJ, Naja WJ.1Department of Psychiatry,

Faculty of Medicine, Lebanese University, Beirut, Lebanon, Over

the past three decades, there has been increasing research with respect to the

relation of religion and mental health disorders. Consequently, the current

article aims to first provide a comprehensive literature review of the

interplay between different domains of religiosity and a wide variety of

categorical anxiety disorders in adults, and secondly, to uncover the major

methodological flaws often yielding mixed, contradictory and unreliable

results. The search was conducted using the PubMed/Medline database and

included papers published between 1970 and 2012, under a rigorous set of

inclusion/exclusion criteria. A total of ten publications were retained as part

of the current study, and three main outcomes were identified: (1) certain aspects

of religiosity and specific religious interventions have mostly had a

protective impact on generalized anxiety disorder (40 % of the studies);

(2) other domains of religiosity demonstrated no association with

post-traumatic stress disorder (30 % of the studies); and (3) mixed

results were seen for panic and phobic disorders.

[iv]

J Relig Health. 2013 Jun;52(2):657-73. doi:

10.1007/s10943-013-9691-4.Mental disorders, religion and spirituality 1990 to

2010: a systematic evidence-based review.Bonelli RM1, Koenig HG.

Author information1Sigmund Freud University, Vienna,

Austria.AbstractReligion/spirituality has been increasingly

examined in medical research during the past two decades. Despite the

increasing number of published studies, a systematic evidence-based review of

the available data in the field of psychiatry has not been done during the last

20 years. The literature was searched using PubMed (1990-2010). We examined

original research on religion, religiosity, spirituality, and related terms

published in the top 25 % of psychiatry and neurology journals according to the

ISI journals citation index 2010. Most studies focused on religion or

religiosity and only 7 % involved interventions. Among the 43 publications that

met these criteria, thirty-one (72.1 %) found a relationship between level of

religious/spiritual involvement and less mental disorder (positive), eight

(18.6 %) found mixed results (positive and negative), and two (4.7 %) reported

more mental disorder (negative). All studies on dementia, suicide, and

stress-related disorders found a positive association, as well as 79 and 67 %

of the papers on depression and substance abuse, respectively. In contrast,

findings from the few studies in schizophrenia were mixed, and in bipolar

disorder, indicated no association or a negative one. There is good evidence

that religious involvement is correlated with better mental health in the areas

of depression, substance abuse, and suicide; some evidence in stress-related

disorders and dementia; insufficient evidence in bipolar disorder and

schizophrenia, and no data in many other mental disorders.

[v]

Can J Psychiatry.

2009 May;54(5):283-91.Research on religion, spirituality, and mental health: a review.

Koenig HG1.Author information1Duke University Medical Center, Durham,

North Carolina 27710, USA. oenig@geri.duke.eduAbstractReligious

and spiritual factors are increasingly being examined in psychiatric research.

Religious beliefs and practices have long been linked to hysteria, neurosis,

and psychotic delusions. However, recent studies have identified another side

of religion that may serve as a psychological and social resource for coping

with stress. After defining the terms religion and spirituality, this paper

reviews research on the relation between religion and (or) spirituality, and

mental health, focusing on depression, suicide, anxiety, psychosis, and

substance abuse. The results of an earlier systematic review

are discussed, and more recent studies in the United States, Canada, Europe,

and other countries are described. While religious beliefs and practices can

represent powerful sources of comfort, hope, and meaning, they are often

intricately entangled with neurotic and psychotic disorders, sometimes making

it difficult to determine whether they are a resource or a liability.

[vi]

Kirkpatrick, L. A. (1997). A longitudinal study of changes in reli- gious

belief and behavior as a function of individual differences in adult attachment

style. Journal for the Scientific Study of Reli- gion, 36 (2), 207-217.

No comments:

Post a Comment